Time Charters

36

Commissions

Commissions

36.1

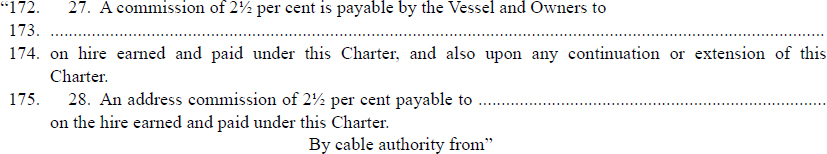

Clauses 27 and 28 of the New York Produce form deal with commissions. By Clause 27, the owners undertake to pay commission to the broker – or brokers – named in Line 173, calculated as a percentage of the hire earned and paid under the charter. Usually, but not always, the named broker is the owners’ broker. The wording of Clause 28 is elliptical. Its effect, however, is thought to be twofold: first, the charterers are given the right to make a deduction from hire of the specified percentage; and second, the charterers undertake to pay the value of the deduction to the person – or persons – named in Line 175. Usually this will be the charterers’ broker.

36.1

Clauses 27 and 28 of the New York Produce form deal with commissions. By Clause 27, the owners undertake to pay commission to the broker – or brokers – named in Line 173, calculated as a percentage of the hire earned and paid under the charter. Usually, but not always, the named broker is the owners’ broker. The wording of Clause 28 is elliptical. Its effect, however, is thought to be twofold: first, the charterers are given the right to make a deduction from hire of the specified percentage; and second, the charterers undertake to pay the value of the deduction to the person – or persons – named in Line 175. Usually this will be the charterers’ broker.

Baltime form

36.2 Under Clause 24 of the Baltime form, the position of the brokers is better than it is under the New York Produce form in three ways:- (1) there is a minimum commission payable, enough to cover expenses plus a reasonable fee for work done;

- (2) there is express provision entitling them to compensation if the full hire is not paid because of a breach of charter by either of the parties to it. The right is against the party in breach;

- (3) they are entitled to compensation of up to one year’s commission if the parties agree to cancel the charter.

Broker’s right to payment of commission

36.3 Prior to the coming into force of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 (the ‘1999 Act’), the broker named in Clause 27 of the New York Produce form could not claim commission from the owners by relying simply on the promise contained in that clause. The owners’ contractual promise to pay commission to the broker could be enforced only by the charterers. They were entitled to enforce that promise because the law regarded them as trustees for the broker of the owners’ promise to pay commission: see Les Affréteurs Réunis v. Walford [1919] A.C. 801 (H.L.). If, however, the charterers refused to sue the owners on the broker’s behalf, the broker could enforce his claim for commission by an action against both the owners and the charterers: see The Panaghia P . See also Atlas Shipping v. Suisse Atlantique on a question of jurisdiction over such a claim. 36.4 The 1999 Act introduced a simpler regime. Subject to certain qualifications, Section 1 of the Act enables a person to sue on a contract to which he is not a party, if a term of the contract purports to confer a benefit on him. One important qualification is that a third party cannot enforce a contract where, on a proper construction of that contract, it appears that the parties did not intend that he should be able to enforce it. The Act, therefore, gives a broker claiming commission under the New York Produce form, and under most usual forms of dry cargo time charter, the right to enforce his claim directly against the owners: see generally Nisshin v. Cleaves . See also for a general review of the effect of the 1999 Act, Chitty, paragraphs 18–088 et seq. 36.5 It must be borne in mind, however, that Section 3 of the Act will allow the owners to raise by way of defence or set-off any matter that “arises from or in connection with the contract and is relevant to the term, and… would have been available to [the owners] by way of defence or set-off if the proceedings had been brought by” the charterers.Broker’s right and obligation to arbitrate a claim for commission

36.6 Section 8 of the 1999 Act provides that where a third party has a right to enforce a term of a contract by operation of Section 1 of the Act, and where the contract contains an arbitration agreement, the third party is obliged to bring his claim in arbitration. The effect of Section 8 is that the third party is treated as if he were a party to the relevant arbitration agreement. In Nisshin v. Cleaves , Colman, J., held that Section 8 permitted and required a broker to arbitrate his claim for commission under the charterparty arbitration clause, even though the terms of the arbitration clause referred only to disputes between “the parties to the charter” or between the “owners” and the “charterers”. The rationale for this is that the broker is, in effect, the statutory assignee of the charterers’ right to require payment by the owners. For an analysis of this judgment, and the issues underlying it, see Parker at .Cancellation or variation of the charter under the 1999 Act

36.7 Section 2 of the 1999 Act provides that, in certain circumstances, where a third party has a right under Section 1 of the Act to enforce a term of a contract, the parties to that contract cannot, by agreement, rescind it or vary it in such a way as to extinguish or alter the third party’s entitlement, without first obtaining the third party’s consent. The relevant circumstances are, as applied to the case of a broker: (a) where the broker has communicated his assent to the term to the owners; (b) where the owners are aware that the broker has relied on the term; or (c) where the owners can reasonably be expected to have foreseen that the broker would rely on the term and the broker has in fact relied on it. In any ordinary chartering transaction, it is likely that all or at least some of these circumstances will exist. 36.8 Clearly, this provision prohibits a variation of the charter designed to prevent the broker from earning commission on an ongoing charter. However, it is less clear whether it affects the parties’ right to agree to the early termination of the charter for other reasons. It is thought that Section 2 does not prohibit such an agreement. An agreement to cancel the charter for that reason, or otherwise redeliver before time, does not extinguish or alter the broker’s right to commission on hire earned and paid. It merely has the practical effect that no further hire is in fact earned or paid and hence no right to commission arises. (The question whether an agreement to terminate the charter early may be prohibited by an implied agreement with the broker is discussed immediately below.) On similar logic, or by extension, it is not thought that Section 2 of the 1999 Act prevents the owners and the charterers from varying a charter so as to amend its duration or rate of hire.An implied obligation on the owners not to prevent the broker earning commission?

36.9 It is clear from the express terms of Clauses 27 and 28 of the New York Produce form that commission is payable only on hire which is both earned and paid under the charter or under any continuation or extension of it. If hire is not paid for the full period of the charter, whether, for example, because of off-hire or because of early termination, the broker does not earn his commission. 36.10 In such circumstances, the question may arise whether any term is to be implied into the agreement between owners and their broker, to the effect that the owners will do nothing to deprive the broker of the commission which he would otherwise earn. The answer is not entirely clear. The House of Lords decided in French v. Leeston Shipping (1922) 10 Ll.L.Rep. 448 that no undertaking is to be implied that the owners will not agree to terminate the charter.

The Clematis was chartered for 18 months, the brokers being entitled to 2 per cent commission from the owners on hire paid and earned. After four months the ship was sold to the charterers and the charter was cancelled by mutual agreement. The brokers sought commission for the remaining 14 months.

The House of Lords held that the brokers were not entitled to it. They could succeed only if there were to be implied into the contract a stipulation that the owners would not in any circumstances terminate the charter by agreement, and there was no necessity for any such implication. Lord Buckmaster said: “The contract works perfectly well without any such words being implied, and, if it were intended on the part of the shipbroker to provide for the cessation of the commission which he earned owing to the avoidance of the charterparty, he ought to have arranged for that in express terms between himself and the shipowner.”

French v. Leeston Shipping (1921) 8 Ll.L.Rep 110 (C.A.), (1922) 10 Ll.L.Rep. 448 (H.L.).

36.11

In reaching their decision, the House of Lords approved an earlier decision of the Court of Appeal in White v. Turnbull, Martin (1898) 3 Com. Cas. 183, in which the charterers, in the course of a 12-month time charter, cancelled the charter, alleging unfitness of the ship for her employment. Litigation between the owners and charterers was settled on terms that the charter should be terminated and the charterers reimbursed for advance hire overpaid. Commission was payable under the charter “on all hire earned” and the brokers claimed commission on hire for the balance of the 12 months of the charter. It was held that on the express wording of the charter, commission was payable only on the hire actually paid, that there was no ‘wilful act’ on the part of the owners which put an end to the charter and that there was no business necessity to imply a term that the charter would not be ended prematurely by agreement.

36.12

In French v. Leeston Shipping, above, Lord Dunedin expressed the view that the position might be different if the premature termination of the charter were brought about “simply and solely to avoid payment of the commission”. That observation, coupled with a similar observation of Lord Buckmaster and the approval of the decision of the Court of Appeal in White v. Turnbull, Martin, would strongly suggest that, in the case of the normal commission arrangements under a time charter, something more is required than a premature termination of the charter as a result of a breach of charter by the owners before brokers could claim damages for loss of commission.

36.13

However, in a number of cases relating to contracts for the sale of ships negotiated by brokers, the courts have held that a term should be implied to protect the broker. Where the broker has negotiated a sale on behalf of his principal as seller, a term is implied into the contract between broker and principal that the principal will not deprive the broker of his commission by breaking the sale contract: see Alpha Trading v. Dunnshaw-Patten (C.A.) and Moundreas v. Navimpex . See also The Manifest Lipkowy (C.A.), where the Court of Appeal rejected the contention that the sellers owed the buyers’ broker an implied duty not to break the sale contract. In these cases, French v. Leeston Shipping was distinguished on two grounds. First, it was said that in French v. Leeston the termination of the contract between principal and third party was by agreement (rather than for breach); second, it was said that that case stood as authority for the proposition that a term will not be implied requiring a person to carry on a particular business in order to preserve his agent’s right to commission.

36.14

It is perhaps doubtful whether the first of these is an adequate basis for distinguishing French v. Leeston. While that case did not itself involve a breach of the charter contract by the owners, the case of White v. Turnbull, Martin, above, seemingly did, in the sense that the settlement under which the charter was terminated prematurely would hardly have been agreed by the owners had the charterers not had strong grounds for contending that the owners were in breach of their obligations as to the fitness of the ship for the employment.

36.15

As was emphasised by May, L.J., in The Manifest Lipkowy, the implication of a term is ultimately a question of the construction of the particular contract. It is submitted that cases in which commission is payable under a time charter “on hire earned and paid” should be distinguished from cases in which commission is payable on the conclusion of a sale – whether on the grounds mentioned above or otherwise. It is accordingly suggested that the owners should not be liable to their broker for terminating the charter, whether by agreement or for breach, unless they have done so for the purpose of avoiding paying commission.

Address commission

36.16 An agreement that there will be an “address commission” gives the charterers the right to make a deduction of that amount from hire. In Fyffes v. Templeman , at page 657, Toulson, J., said: “There is certainly nothing unusual about a shipowner and ship charterer agreeing that the charterer should receive what is misleadingly termed ‘address commission’, but is in reality a discount or rebate on the hire”. Although the address commission is payable only on hire “earned” as well as paid, it is thought that the charterers are entitled to deduct address commission from hire paid in advance. 36.17 Clause 28 envisages that “address commission” will be payable to a named third party. Where a recipient has been agreed, it is implicit that he is to be paid by the charterers. In many cases, however, there is no agreement that the address commission will be paid to any particular third party. Where that is the case, the agreement for an “address commission” is in practice simply a rebate from hire.U.S. Law

Commissions

36A.1 The services performed by a broker in arranging a charter are not considered maritime for jurisdictional purposes. Consequently, claims by brokers for commissions ordinarily are not maritime or admiralty causes and do not give rise to a maritime lien in favor of the broker. See The Thames, 10 F. 848 (S.D.N.Y. 1881); Taylor v. Weir, 110 F. 1005 (D.Or. 1901); Andrews & Co. v. United States, 124 F. Supp. 362, 1954 AMC 2221 (Ct.Cl. 1954), aff’d 292 F.2d 280 (Ct.Cl. 1954); Marchessini & Co. (New York) v. Pacific Marine Co., 227 F. Supp. 17, 1964 AMC 1538 (S.D.N.Y. 1964); European-American Banking Corp. v. The Rosaria, 486 F. Supp. 245, 255 (S.D. Miss. 1978); and Boyd, Weir & Sewell Inc. v. Fritzen-Halcyon Lijn Inc., 1989 AMC 1159 (S.D.N.Y. 1989). 36A.2 Equally, a claim for a broker’s commission will not support a maritime attachment under Rule B. Harvey Mullion & Co. Ltd. v. Caverton Marine Ltd., 2008 A.M.C. 2361 (S.D.N.Y. 2008) (citing Shipping Financial Services Corp. v. Drakos, 1998 A.M.C. 1578, 1585 (1998), which held that a ship brokerage contract was not sufficiently maritime in nature under Exxon Corp. v. Central Gulf Lines, Inc., 500 U.S. 603 (1991)). 36A.3 But see Naess Shipping Agencies Inc. v. SSI Navigation Inc., 1985 AMC 346 (N.D.Cal. 1984), where the court held that there was admiralty jurisdiction of a broker’s claim for commissions. In that case, the broker had arranged contracts for the construction and subsequent charter of four container vessels. The court found that since the broker’s duties were to extend throughout the period of performance of the construction contracts and charters, and because the broker was to be paid commissions over the 14-year life of the contracts, there was admiralty jurisdiction. The court distinguished other decisions holding that there is no admiralty jurisdiction over a broker’s claim for commissions on the basis that, in the present case, it could not be said that the contracts were preliminary to a maritime contract; rather, because the broker’s duties were to extend throughout the life of the contracts, the brokerage contract itself was deemed to be maritime in nature. 36A.4 Since the broker is not a party to the charter, it cannot claim a right of action under it to recover commissions. Congress Coal and Transp. Co. Inc. v. International S.S. Co., 1925 AMC 701 (Penn. 1925). Moreover, a charterer’s attempt to enforce the broker’s rights in an action under the charter has been rejected. In two cases, arbitrators held that they lacked jurisdiction to award broker’s fees since the claim did not constitute a dispute between the parties to the charter. The Caribbean Trader, SMA 41 (Arb. at N.Y. 1964) and Jugotanker-Turisthotel v. Mt. Ve Balik Kurumu, SMA 1133 (Arb. at N.Y. 1977). 36A.5 The broker’s entitlement to commissions is entirely dependent upon the language of the contract authorizing the commissions. Unless the charter provides otherwise, the broker may recover commissions only to the extent that hire is actually paid under the charter. Lougheed & Co. Ltd. v. Suzuki, 216 App. Div. 487, 215 N.Y.S. 505, aff’d 243 N.Y. 648, 152 N.E. 642 (1926); Caldwell Co. v. Connecticut Mills, 225 App. Div. 270, 273, 232 N.Y.S. 625, aff’d 251 N.Y. 565, 168 N.E. 429 (1929); Tankers Int’l Navigation Corp. v. National Shipping & Trading Corp., 499 N.Y.S. 2d 697, 1987 AMC 478 (A.D. 1 Dept. 1986). 36A.6 In Lougheed, above, the charter provided that a commission was due “on the monthly payment of hire.” The charterer paid no hire because of the owner’s failure to make a timely delivery of the vessel. The court dismissed the broker’s claim for commissions and stated that the brokerage clause “indicated a clear intention to pay commissions only on the monthly payment of hire when received.” (216 App. Div. at 492.) According to the court, “commissions were payable to [the broker] only as and when monthly hire for the steamship was received. …” (Id. at 493) 36A.7 In Tankers Int’l, above, the broker claimed commissions on funds paid by the charterer to the owner to settle the latter’s claim for unpaid hire. While the court stated that a factual question was raised as to whether the obligation to pay commissions survived the charterer’s default, the court observed that as a matter of law, the payment of settlement funds was not the equivalent of the payment of hire as earned under the charter. According to the court:

Even had the shipowners recovered the full amount of hire sought by their claims, it is well settled that a broker is not entitled to recover commissions merely because his principal has secured a benefit equivalent to what he would have received had the contract been performed. [499 N.Y.S. 2d at 701]

36A.8

In Rountree Co. v. Dampskibs Aktieselskabet Oy II (The Hinnoy), 1934 AMC 26 (City Ct. N.Y. 1933), a broker’s claim for commissions based on the earnings under a substitute charter entered into by the charterer in mitigation of damages under a charter which the broker had arranged and which the charterer had cancelled was denied.

36A.9

Where a charterparty contains a provision that commissions are payable upon its execution, a broker is entitled to receive such commissions even if no hire is earned. See Vellore S.S. Co. Ltd. v. Steengrafe, 229 F. 394 (2d Cir. 1915).