37

Shelltime

Shelltime

37.1

This chapter is intended mainly as a guide to cases decided by the English courts on this form and on other tanker time charter forms. Tanker charter cases have therefore been covered in detail even where they have already been dealt with in the earlier chapters of the book. The chapter takes the Shelltime 4 form as its framework. The Shelltime 4 form was issued in December 1984. It was revised in December 2003 so as to reside on BIMCO’s on-line document service “idea”, which hosts a variety of non-BIMCO documents as well as BIMCO’s own published forms. Shelltime 4 (2003 revision) thus now resides on “idea” as “the first ‘living’ time charterparty” (per Grant Hunter, Head of Documentary Department, BIMCO, writing in Legal Issues Relating to Time Charterparties, Informa (2008), paragraph ). This apparently allows Shell to update the form from time to time. Any such updating may result in a new “version number” for the document, “depending on its significance”. It is not difficult to envisage how this could result in problems, and no doubt broking practice must take careful account of the possibility for error or confusion, although we understand that in fact Shell has not updated the form since April 2006. For complete clarity here, this chapter takes as its text Shelltime 4 (2003 revision, version 1.1 Apr 06), as published on “idea” on 1 April 2014, and that is the version reproduced at F4 in the Forms section at the end of this book.

“SHELLTIME 4”

Issued December 1984 amended December 2003, Version 1.1 Apr 06

37.2

Questions arising in connection with the formation of the contract and with the parties to the contract are dealt with earlier in this book in and 2, respectively.

37.2

Questions arising in connection with the formation of the contract and with the parties to the contract are dealt with earlier in this book in and 2, respectively.

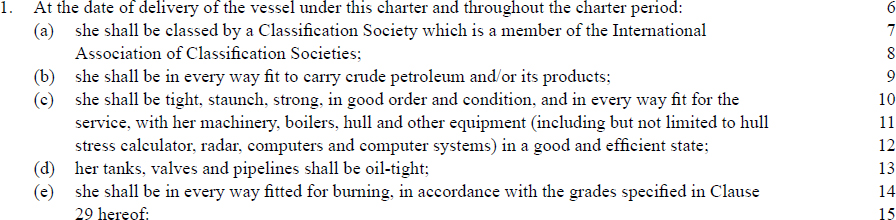

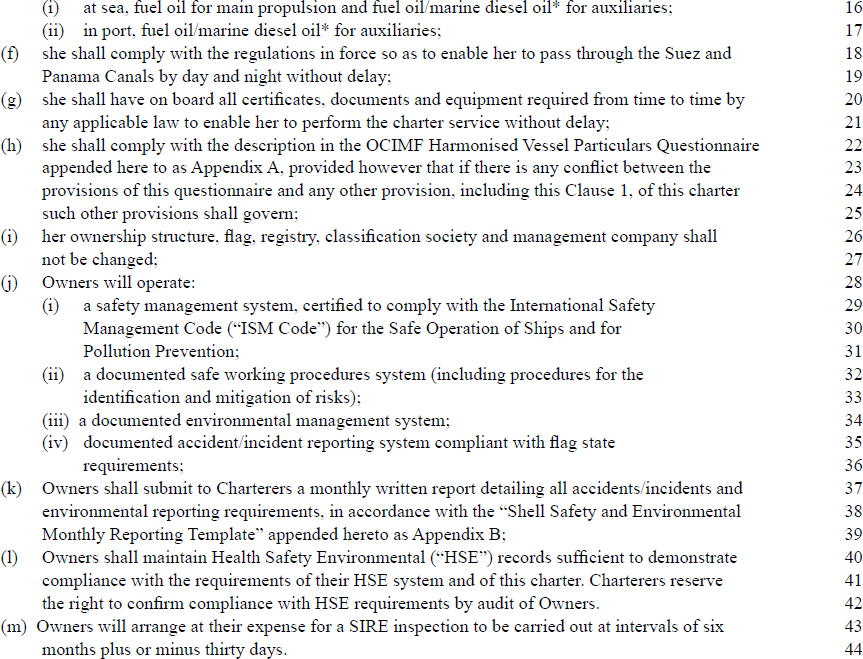

37.3 Clause 1 – Description and Condition of Vessel; Safety Management

Obligations upon delivery

37.4

Clauses 1(a) to (g) of Shelltime 4, to the extent that they contain undertakings as to the state and condition of the ship at the time of delivery, and Clause 1(h), to the extent it requires that the ship shall comply with the details set out in the attached Vessel Questionnaire, all form part of the description of the ship. Also forming part of the description are the name of the ship (or in the case of a newbuilding, the yard and yard number: see The Diana Prosperity ) to be inserted in Line 3, as well as the stipulations as to personnel contained in Clause 2(a). If a ship is misdescribed and the misdescription is discovered by the charterers before or upon delivery, the question whether delivery may be refused or whether the charterers must accept delivery and claim damages depends in part on which element of the description is inaccurate and in part on the seriousness of the misdescription. This question is dealt with at to , et seq. and et seq., above.

37.5

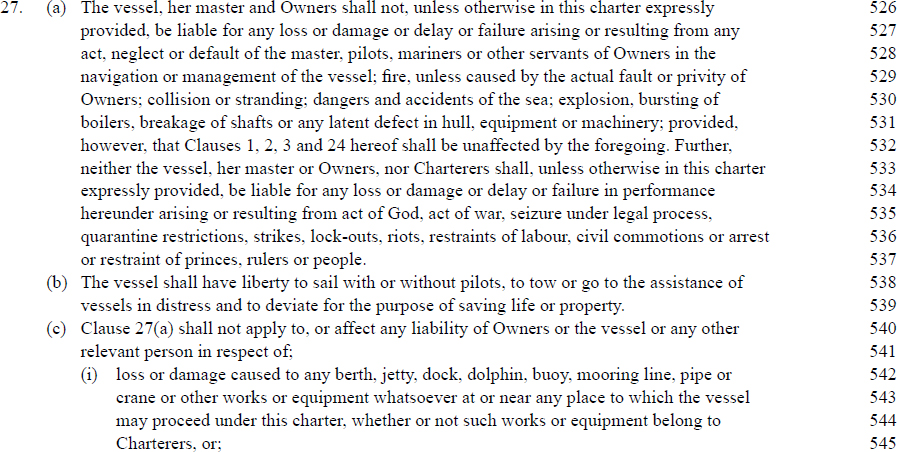

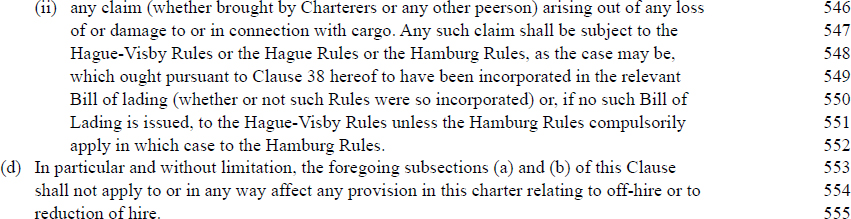

The stipulations in Clause 1 (and Clause 2(a)), to the extent they contain undertakings applicable at the date of delivery, impose absolute obligations (see paragraph G.1, below), so that it is irrelevant to any question of compliance or breach whether due diligence was exercised or not: see The Fina Samco , per Colman, J., at page 158, the facts of which are set out under Clause 3 below, and The Trade Nomad , (C.A.); and see generally on description of the ship , above. But in regard to claims arising out of “any loss of or damage to or in connection with cargo”, if they are subject to the Hague or Hague-Visby Rules pursuant to Clause 27(c)(ii), the effect of Article IV, rule 1 of the Rules will be to reduce the obligation of seaworthiness from an absolute obligation to an obligation to exercise due diligence to make the ship seaworthy. If, under Clause 27(c)(ii), such claims are subject to the Hamburg Rules, then the owners will not be liable if they show, under Article 5(1) that they, their servants and agents took all measures that could reasonably be required to avoid the occurrence and its consequences. (Clause 27 is quoted at paragraph , below, and Clause 27(c)(ii) is discussed in and .)

37.6

The general requirement in Clause 1(c) that the ship shall be “tight, staunch, strong… and in every way fit for the service…” constitutes an express undertaking of seaworthiness. This has been so held in the case of the New York Produce charter in which the wording is almost identical save that the word “fitted” is used instead of “fit”, a distinction which is not thought to be material. In The Derby , at page 641, Hobhouse, J., whose decision was upheld by the Court of Appeal at , in considering the words “tight, staunch, strong and in every way fitted for the service” in Line 22 of the New York Produce form, said: “When one is concerned, as here, with a charter-party which is going to run for a considerable period of time and gives to the charterer very wide options as to the orders he may give to the owners, questions arise as to the extent to which the owners are required, at the time of delivery, to anticipate and provide in advance for every contingency… With regard to ‘fitness for the service’, as used in the NYPE form, the fitness must be fairly generally construed as otherwise one may be laying the owners open to having to fulfil conflicting and inconsistent obligations depending on which contingency is taken into account. So, while I do not accept owners’ argument that to be unfit the vessel must be foredoomed to being unable properly to carry out the charter-party obligations… I do not accept either charterers’ argument that any subsequent delay or any necessity to make some alteration to the vessel or its equipment, etc., automatically shows an initial lack of fitness.”

37.7

Such considerations will be most relevant to matters not specifically dealt with in Clause 1 of the Shelltime 4 and, by contrast, less relevant in general to those matters which are specifically dealt with as, for example, under Clause 1(d), (e) and (h). But in the case of a wide-ranging undertaking, such as that in Clause 1(g), that at the date of delivery the ship “shall have on board all certificates, documents and equipment required from time to time by any applicable law to enable her to perform the charter service without delay”, questions may well arise as to the extent to which the owners are required to anticipate every contingency. For authorities on fitness and on documents required to be on board to comply with this obligation, see et seq., above. In The Elli and The Frixos (C.A.), Clause 1(g) of the original Shelltime 4 form was held to be a continuing promise, applicable throughout the charter, although Clause 1 was then introduced only by the words “At the date of delivery under this charter” (contrast et seq., below). That reading of Clause 1(g) seems, with respect, doubtful. It is thought the better reading was that ‘required from time to time’ in Clause 1(g) described the character of the documents promised by Clause 1(g), rather than the time at which they were promised.

37.8

Questions of fitness are prima facie questions of fact. A deficiency in equipment which has no effect on the safety of the ship, her efficient operation, or the security or integrity of her cargo, and is of no real commercial significance, may not make the ship unfit for the service even though, by reason of the deficiency, the equipment in question does not comply with the requirements of the charter.

The

Arianna was time chartered for a period of 10 years on the Essotime form for worldwide trading. The charter provided by Clause 3: “… hire to commence when written notice from the Master has been given to the Charterer… that the Vessel is at its disposal… the Vessel being then ready with holds and cargo tanks, pipes and pumps clear and clean to Charterer’s Inspector’s satisfaction and in every way fitted for the service and the carriage of [general products], and being on delivery tight, staunch and strong and with pipe lines, pumps and heater coils in good working condition, so far as the same can be attained by the exercise of due diligence…”. The charter further provided by an additional Clause 69: “Owner to at all times maintain tank cleaning system in good order such that 6 machines can run simultaneously, at seawater temperature of 180´F at 170 PSI pressure.”

When the ship was tendered for delivery, the charterers declined to accept her on the ground that her tank-cleaning system did not comply with the requirements of the charter. Arbitrators found that while the vessel’s six tank-cleaning machines could run simultaneously at the temperature and pressure required by Clause 69, that clause, properly construed, required that the six machines should be capable of running simultaneously while the ship was in port and was at the same time heating cargo destined for other ports and this the ship could not achieve. The arbitrators found further that the pattern of trading under the charter might have been such that this situation would never have arisen and, even if it did, the ship could always run four cleaning machines simultaneously; the only consequence of the deficiency would have been some minor delay. The arbitrators held that, despite the breach of Clause 69, the ship was nevertheless ‘in every way fitted for the service’ and the charterers’ refusal to take delivery was unjustified.

On appeal, it was argued on behalf of the charterers that in the light of the deficiency in the tank-cleaning system, the ship could not as a matter of law be “fitted for the service”. In rejecting this submission Webster, J., held that the question of fitness was primarily one of fact. Whether the ship was fit or not depended upon the significance of the defect and it was implicit in the arbitrators’ award that they regarded the deficiency in this case as of no real significance in a commercial sense.

The Arianna .

“and throughout the charter period”

37.11

These words appear in Line 6, introducing Clause 1, and also in Line 45, introducing Clause 2(a). They were not in the original Shelltime 4. The question arises whether they render Clauses 1(a) to 1(h) not only absolute undertakings applicable at the date of delivery, but also absolute, continuing undertakings that the ship will always possess all of those attributes in full, no matter what happens during the charter. It is thought that cannot be the correct reading. It would involve the owners in an extravagant promise and is contradicted by Clause 3(a), by which the owners undertake only an obligation to exercise due diligence to maintain or restore the ship (see et seq., below).

37.12

The better reading of Line 6, it is suggested, is that “throughout the charter period” applies only to Clause 1, items (i) to (m), which were added to the standard form at the same time, and each of which is by nature a promise by the owners as to how the ship will be operated during the charter rather than a promise that a particular state of affairs will exist at the moment of delivery (on which, in respect of Clause 1(g), see paragraph , above). Reading “At the date of delivery” in Line 6 with Clause 1(a) to (h) and “throughout the charter period” with Clause 1(i) to (m) recognises and gives effect to that clear difference in the nature of those sets of items. Thus, the sense of Line 6, it is thought, is “At the date of delivery of the vessel under this charter and, in the case of (i) to (m) below, throughout the charter period”. It may seem remarkable that Clause 1 (and, by parity of reasoning, Clause 2(a)) should mix together provisions referable to the owners’ obligations on delivery and provisions as to what will be required during the charter period. However, that is something Shelltime 4 has always done. Clause 2 has always contained delivery obligations (Clause 2(a)) and ongoing obligations (Clause 2(b)) and Clause 3 has always mixed together matters of ongoing maintenance and repair (Clauses 3(a) and 3(c)) and a provision concerned only with breach of the owners’ delivery obligations (Clause 3(b)), all under the marginal title (in the circumstances a misleading one), “Duty to Maintain”.

37.13

The undertakings in Clauses 1(i) to (m) which, thus, apply “throughout the charter period”, require the owners to follow certain specific management and reporting systems and do not require particular elaboration. However, it should be noted that they will not apply directly so as to determine the owners’ liability arising out of any loss of or damage to or in connection with cargo. Any such claim, brought by the charterers or by any other person, will be subject to the Hague, Hague-Visby or Hamburg Rules pursuant to Clause 27(c)(ii). That said, if the owners have failed to comply with Clauses 1(i) to (m), that may have an impact on whether they can establish a defence to such a claim under the applicable Rules.

Oil major approvals

37.14

At Clause 43 (see paragraph , below) Shelltime 4 contains, as did the charter in The Seaflower (No. 2) below, an express right in the charterers to terminate the charter if the ship becomes unacceptable to “any Oil Major”. The identity of these dominant oil companies is discussed at paragraph .

37.15

Additional clauses describing the ship as having certain oil major approvals at the date of the charter may be construed as conditions entitling the charterers to treat the contract as discharged if the ship does not have the stated approvals at that time. Oil major approvals, like class, are matters of status rather than seaworthiness: see The Seaflower (No. 2) and The Rowan, below (in which Longmore, L.J., suggested at [16] in the Court of Appeal report that this aspect of the description of the ship at the outset will ‘normally’ be a condition). It has become common to incorporate clauses drawing on provisions of the SIRE tanker vetting system established by the Oil Companies International Maritime Forum (OCIMF); see, for example, The Savina Caylyn , in which express provision was made as to the circumstances in which difficulties with vetting approvals were to entitle the charterers to terminate the charter (in that case, three consecutive oil major vetting failures). It should also be noted that oil majors have not for some years now issued (as such) standing approvals of vetted ships and references to oil major approvals may need to be construed accordingly as connoting ‘SIRE inspected/vetted and not disapproved’ (see The Rowan and (C.A.)).

37.16

A clause by which the owners undertake to obtain a particular oil major approval within a certain time may also be construed as a condition, if the necessary implication from the contract as a whole is that it was the parties’ intention to give the charterers a right to cancel if the approval was not obtained within the period.

The

Seaflower was chartered on the Shelltime form for a period of 11 to 12 months. An additional “Majors Approval Clause” stated that the ship had Mobil, Conoco, BP and Shell approvals, and went on:

“… Owners guarantee to obtain within 60 (sixty) days Exxon approval in addition to present approvals. On delivery date hire rate will be discounted USD250 (two hundred and fifty) for each approval missing, ie Mobil, Conoco, BP, Shell, Exxon.

If for any reason during the time-charter period, Owners would loose [sic] even one of such acceptances they must advise Charterers at once and they must reinstate the same within 30 (thirty) days from such occurrence failing which Charterers will be at liberty to cancel charterparty or to maintain same at reduced rate as stipulated above.”

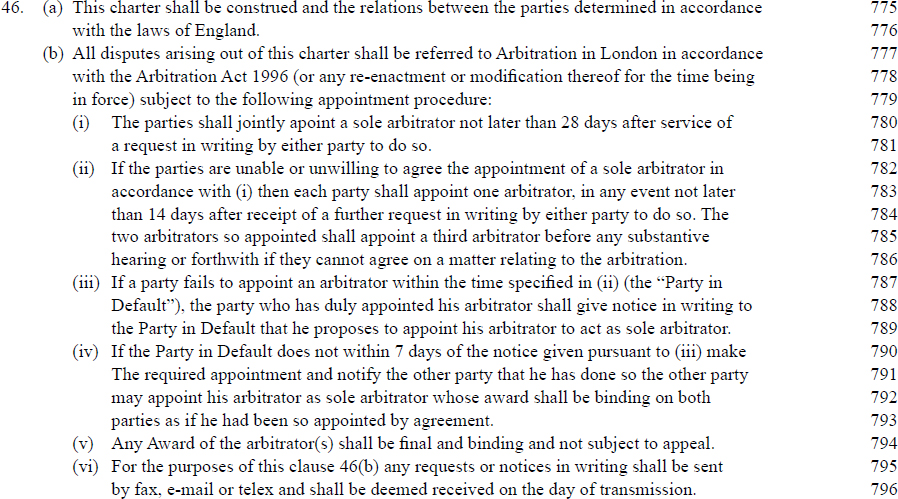

The owners failed to obtain the Exxon approval within 60 days and the charterers cancelled. The owners contended that a right of cancellation arose only if the owners lost an approval during the period of the time charter and failed to reinstate it within 30 days.

It was held by the Court of Appeal, reversing Aikens, J., that the obligation to obtain the Exxon approval within 60 days was a condition, breach of which entitled the charterers to treat the contract as at an end. If that provision was not so classified, it lost nearly all its effect and gave rise to uncertainty; there was no commercial or other reason for treating a failure to obtain the Exxon approval differently from a failure to renew the other approvals and the word ‘guarantee’ emphasised the importance attached to the term, even though on its own the word would have been insufficient to support a conclusion that the term was a condition of the contract.

The Seaflower (No. 2) (C.A.).

(See also the report at

on the charterers’ alternative claim on the footing that the above term was not a condition but an intermediate term only.)

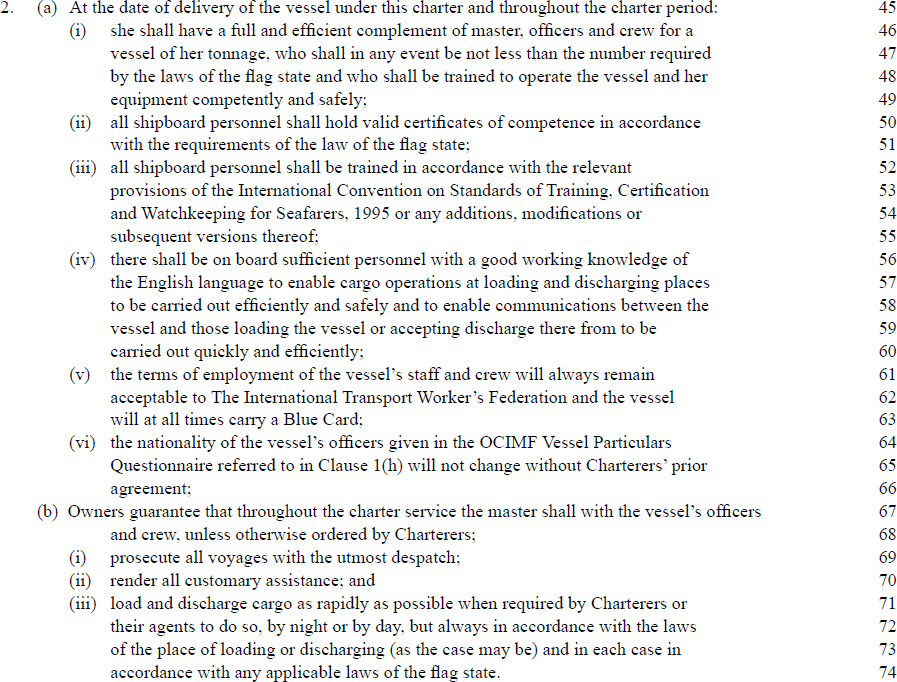

37.17 Clause 2 – Shipboard Personnel and their Duties

Obligations upon delivery

37.18

The detailed requirements in Clause 2(a)(i) to (iv) as to the adequacy, competence and efficiency of the crew at the date of delivery, which are also part of the description of the ship, are again absolute in nature: see under Clause 1, above. Clause 2(a)(i) is equivalent to the undertaking of seaworthiness at the time of delivery that is implied at common law, insofar as it relates to the ship’s crew: see paragraph , above.

“and throughout the charter period”

37.19

As in Line 6 introducing Clause 1, see et seq., above, it is thought these words in Line 45 do not convert the requirements of Clause 2(a)(i) to (iv) into continuing, absolute promises, contradicting Clause 3(a), but rather apply only to the promises in Clause 2(a)(v) and (vi) which were added to Shelltime 4 at the same time. Those promises are that the ship’s officers and crew will always be employed on terms acceptable to the ITF, that the ship will always carry an ITF Blue Card, and that the nationality of the ship’s officers given in the Vessel Questionnaire referred to in Clause 1(h) will not change during the charter except with the charterers’ prior agreement. In other words, Line 45 is to be read as “At the date of delivery of the vessel under this charter and, in the case of (v) and (vi) below, throughout the charter period:”.

37.20

Like the promises in Clause 2(a)(v) and (vi), the ‘guarantee’ in Clause 2(b) is not concerned with the state of affairs at the date of delivery, but with the duties of the ship’s officers and crew throughout the charter service. It is submitted that the use of the word “guarantee” in Clause 2(b) indicates only that the obligation is intended to be absolute and not that it should be construed as a condition rather than an intermediate term: for the significance of this distinction, see paragraphs G.2 and G.18, below. That said, in an early case under a tanker time charter, Pennsylvania Shipping v. Cie Nationale de Navigation (1936) 55 Ll.L.Rep. 271 (the facts of which are set out at paragraph , above), it was held the use of the word “guaranteed” in relation to the diameter of the ship’s cargo lines and the position of heating coils gave the term the status of a condition.

37.21

For comments on the obligations to prosecute all voyages with the utmost despatch and render all customary assistance, see , above.

37.22 Clause 3 – Duty to Maintain

| 3. |

(a) Throughout the charter service Owners shall, whenever the passage of time, wear and |

|

| |

tear or |

75 |

| |

any event (whether or not coming within Clause 27 hereof) requires steps to be taken to |

76 |

| |

maintain or restore the conditions stipulated in Clauses 1 and 2(a), exercise due diligence so to |

77 |

| |

maintain or restore the vessel. |

78 |

| |

(b) If at any time whilst the vessel is on hire under this charter the vessel fails to comply with the |

79 |

| |

requirements of Clauses 1, 2(a) or 10 then hire shall be reduced to the extent necessary to |

80 |

| |

indemnify Charterers for such failure. If and to the extent that such failure affects the time taken |

81 |

| |

by the vessel to perform any services under this charter, hire shall be reduced by an amount |

82 |

| |

equal to the value, calculated at the rate of hire, of the time so lost. |

83 |

| |

Any reduction of hire under this sub-Clause (b) shall be without prejudie to any other remedy |

84 |

| |

available to Charterers, but where such reduction of hire is in respect of time lost, such time |

85 |

| |

shall be excluded from any calculation under Clause 24.86 |

(c) If Owners are in breach of their obligations under Clause 3(a), Charterers may so notify Owners |

87 |

| |

in writing and if, after the expiry of 30 days following the receipt by Owners of any such notice, |

88 |

| |

Owners have failed to demonstrate to Charterers’ reasonable satisfaction the exercise of due |

89 |

| |

diligence as required in Clause 3(a), the vessel shall be off-hire, and no further hire payments |

90 |

| |

shall be due, until Owners have so demonstrated that they are exercising such due diligence. |

91 |

| |

(d) Owners shall advise Charterers immediately, in writing, should the vessel fail an inspection by, |

92 |

| |

but not limited to, a governmental and/or port state authority, and/or terminal and/or major |

93 |

| |

charterer of similar tonnage. Owners shall simultaneously advise Charterers of their proposed |

94 |

| |

course of action to remedy the defects which have caused the failure of such inspection. |

95 |

| |

(e) If, in Charterers reasonably held view: |

96 |

| |

(i) failure of an inspection, or, |

97 |

| |

any finding of an inspection, |

98 |

| |

referred to in Clause 3(d), prevents normal commercial operations then Charterers have the |

99 |

| |

option to place the vessel off-hire from the date and time that the vessel fails such inspection, or |

100 |

| |

becomes commercially inoperable, until the date and time that the vessel passes a re-inspection |

101 |

| |

by the same organisation, or becomes commercially operable, which shall be in a position no |

102 |

| |

less favourable to Charterers than at which she went off-hire |

103 |

| |

(f) Furthermore, at any time while the vessel is off-hire under this Clause 3 (with the exception of |

104 |

| |

Clause 3(e)(ii), Charterers have the option to terminate this charter by giving notice in writing |

105 |

| |

with effect from the date on which such notice of termination is received by Owners or from any |

106 |

| |

later date stated in such notice. This sub-Clause (f) is without prejudice to any rights of |

107 |

| |

Charterers or obligations of Owners under this charter or otherwise (including without limitation |

108 |

| |

Charterers’ rights under Clause 21 hereof). |

109 |

Sub-Clause (a)

37.23

Unlike the obligations under Clauses 1 and 2 of the Shelltime 4, the obligation to maintain under Clause 3(a) is not ‘absolute’. The owners’ obligation is only to exercise due diligence. The obligation to maintain under Clause 2 of the Shelltime 3 form was similarly limited to the exercise of due diligence. Whether, if other terms of the charter impose on the owners an obligation to carry out specific work, such obligations are absolute or limited to the exercise of due diligence, depends upon the construction of the charter as a whole.

The

Bridgestone Maru No. 3 was chartered for one year on the Shelltime 3 form, Clause 2 of which provided: “Owners shall, before and at the date of delivery of the vessel under this charter, exercise due diligence to make the vessel in every way fit to carry fully refrigerated Butane and/or Propane and… in every way fit for… service … Owners undertake that throughout the period of service under this charter they will … require steps to be taken to maintain the vessel as stipulated in clause 1 hereof… ” Clause 1,

inter alia, required the ship to be in class at the date of delivery. By an additional typewritten clause the charter further provided: “Owners agree at a subsequent date that booster pump(s) shall be fitted …”

The charterers contended that, on a proper construction of the charter, terms were to be implied imposing on the owners an ‘absolute’ obligation that the booster pump would be properly and carefully installed and that the approval of the ship’s classification society would be sought and obtained for that installation.

Hirst, J., in rejecting this contention, said at page 76: “In my judgment, business efficacy is fully met by the express obligation to exercise due diligence, and there is no necessity to superimpose more rigorous terms specifically applicable to the mode of installation and the class aspects of the booster pump. I therefore hold that the implied terms are not made good and that the defendants’ obligations in these respects are to be found in cl. 2, though I should add that I think that the due diligence obligation in relation to class can properly be construed as including an obligation to exercise due diligence to seek and obtain any requisite class approval for any given installation.”

The Bridgestone Maru No. 3 .

Sub-Clause (b)

37.29

The provisions in Clause 3(b) for reduction in hire apply to deficiencies in respect of the requirements of Clause 1(a) to (h) or Clause 2(a)(i) to (iv) existing at the time of delivery, but not to any such deficiencies which arise only after delivery: see The Fina Samco, below. The provisions of Clause 3(b) also apply to deficiencies constituting a breach of Clause 10 (space available to charterers) which occur at any time and, it is suggested, likewise to a failure at any time to comply with the ongoing requirements of Clause 1(i) to (m) or Clause 2(a)(v) or (vi).

The

Fina Samco was chartered on the original Shelltime 4 form. In the course of the charter she was ordered to discharge crude oil at two Japanese ports, Tomakomai and Nagoya. The ship arrived at Tomakomai on 21 October 1990 and commenced discharge at 0112 on 22 October. Between the time of commencing discharge and 0848 on 22 October, there was a total of 11 stoppages of discharge, ranging in length from 6 minutes to 36 minutes, due to boiler trouble. By 0830 the stoppages had amounted in aggregate to 3 hours 2 minutes. After 0848 the stoppage continued whilst attempts were made to diagnose the cause of the trouble. At 1115 on 22 October the berthing master ordered the ship to leave the berth due to deteriorating weather and sea conditions.

The arbitrator found that even if the boiler problem had not arisen, the berthing master would have ordered the ship off the berth at that time. The ship then lay off the berth unable to return because of the weather and sea conditions until 8 November. In the meantime, the cause of the trouble was identified and repairs were carried out. The arbitrator found that the defect had not existed at the time of delivery of the ship. The charterers claimed that the vessel was off hire from 22 October until 8 November (see paragraph

, below, for a discussion of the off-hire aspects of the case). In the alternative, the charterers relied on the indemnity provided by Clause 3(b), which was then Clause 3(ii) of the form, contending that there was loss of time caused by the failure of the ship to comply with the requirements of Clause 1 of the charter.

It was held by Colman, J., and the Court of Appeal, that Clause 3(ii), as it was then, applied only to loss suffered by the charterers from breaches of Clauses 1, 2(a) or 10 and thus to deficiencies in the Clauses 1 or 2(a) characteristics which existed at the time of delivery under the charter. It did not apply to such deficiencies arising after the date of delivery and therefore did not apply to the boiler defects which had caused the stoppages in the discharging operation. (Clauses 1 and 2(a) of the original Shelltime 4 form contained only delivery requirements and nothing equivalent to what is now Clause 1(a)(i) to (m) or Clause 2(a)(v) and (vi).)

The Fina Samco and

(C.A.).

Sub-Clause (c)

37.32

Clause 3(c) entitles the charterers to put the ship off hire if the owners have failed to exercise due diligence to restore full fitness, have been notified by the charterers of that failure and then fail within 30 days to demonstrate to the charterers’ reasonable satisfaction that due diligence is now being exercised. A notice under Clause 3(c) alleging a breach of the owners’ obligations under Clause 3(a) must identify in what way the owners are in breach, so that the nature of the charterers’ complaint is known. Tuckey, J., so held in Bocimar v. Anders Wilhelmsen (The Ensor, Permeke and Vesalius) (1993), unreported, affirming the decision of an arbitrator that it was necessary to imply such a term in Clause 3(iii), the equivalent of Clause 3(c) in the original Shelltime 4 form, in order to give the contract business efficacy. In that case, under a charter on the original Shelltime 4 form, the charterers had in the past communicated complaints to the owners regarding deficiencies in the hatch covers, which they alleged made the ships unfit to carry oil cargoes. Subsequently the charterers gave notices to the owners under Clause 3(iii), which referred to complaints, but did not specifically refer to the earlier complaints. It was held by the arbitrator that the notices were invalid and that consequently the ships were not put off hire under Clause 3(iii) and Tuckey, J., affirmed his decision.

Sub-Clauses (d) and (e)

37.33

In an age of ever-increasing vigilance as to the condition of the world tanker fleet, these provisions, which were not in the original Shelltime 4, grant the charterers important rights should external agencies or commercial parties find fault with the ship on inspection. The general scheme of the provisions is clear enough: the owners agree to notify the charterers at once if an inspection is failed, advising the charterers of their plan to set things right; if the charterers reasonably judge that their normal commercial operations are prevented, they may put the ship off hire. There are, however, two ambiguities in the drafting that could give rise to dispute.

37.34

First, Clause 3(d) applies if the ship fails “an inspection by, but not limited to” stated types of entity. The phrase “by, but not limited to” leaves it unclear whose inspections other than those of the stated types will trigger the owners’ obligations. Moreover, there could no doubt be costly and time-consuming argument over who is or is not a “major charterer” or over how wide is the net of “similar tonnage”. It is, perhaps, possible that Clause 3(e) will assist in construing these provisions, leading to a conclusion that all inspections failure of which is liable to render the ship “commercially inoperable”, and only such inspections, fall within Clause 3(d). It would, though, be more helpful if Clause 3(d) itself were clear. It has become common for additional clauses to be incorporated which refer, as does Clause 43, to “any Oil Major” (as to which see paragraph , below) and draw on the SIRE tanker inspection and vetting system established by the Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF); see, for example, The Savina Caylyn .

37.35

Second, Clause 3(e)(ii) entitles the charterers to put the ship off hire when “any finding of an inspection, referred to in Clause 3(d)” prevents normal commercial operation of the ship. It is unclear whether that is limited to inspections that have been failed. For example, a major charterer of similar tonnage might find on inspection defects in equipment that is often important but not to that charterer. The owners have no obligation to report the inspection result or provide an action plan under Clause 3(d), but the defect could disrupt the charterers’ normal commercial operations. It is suggested that Clause 3(e)(ii) probably does not then apply and the charterers must rely on Clause 3(a) and (c), or the off-hire clause, which may be sufficient to protect their interests, but the wording of Clause 3(e) is not as clear as it could be.

Sub-Clause (f)

37.36

This confers on the charterers a right to terminate the charter by notice to the owners if the ship is “off-hire under this Clause 3 (with the exception of Clause 3(e)(ii))”.

37.37

That is straightforward, so far as Clause 3(c) and Clause 3(e) are concerned. But is Clause 3(f) engaged by Clause 3(b)? It is perhaps tempting to say so, since only Clause 3(e)(ii) is expressly excluded from the operation of Clause 3(f). It is suggested that is not the correct reading, however. Clause 3(b) does not refer to “off-hire” or to putting the ship off hire, but operates to extend the charterers’ rights of set-off against hire, where there has been a breach of Clause 1, 2(a) or 10. (See on rights of set-off against hire.) In The Fina Samco at first instance, Colman, J., indicated that in a case falling within Clause 3(ii), as it was in the original Shelltime 4 form, off-hire was governed by the off-hire clause (Clause 21), in other words not by Clause 3; see paragraph , above.

37.38 Clause 4 – Period, Trading Limits and Safe Places

| 4. |

(a) Owners agree to let and Charterers agree to hire the vessel for a period of ____ |

110 |

| |

plus or minus ____ days in Charterers’ option, commencing from the time and date of delivery |

111 |

| |

of the vessel, for the purpose of carrying all lawful merchandise (subject always to Clause 28) |

112 |

| |

including in particular; |

113 |

| |

____ |

114 |

| |

in any part of the world, as Charterers shall direct, subject to the limits of the current British |

115 |

| |

Institute Warranties and any subsequent amendments thereof. Notwithstanding the foregoing, |

116 |

| |

but subject to Clause 35, Charterers may order the vessel to ice-bound waters or to any part of |

117 |

| |

the world outside such limits provided that Owner’s consent thereto (such consent not to be |

118 |

| |

unreasonably withheld) and that Charterers pay for any insurance premium required by the |

119 |

| |

vessel’s underwriters as a consequence of such order. |

120 |

| |

(b) Any time during which the vessel is off-hire under this charter may be added to the charter |

121 |

| |

period in Charterers’ option up to the total amount of time spent off-hire. In such cases the rate |

122 |

| |

of hire will be that prevailing at the time the vessel would, but for the provisions of this Clause, |

123 |

| |

have been redelivered. |

124 |

| |

(c) Charterers shall use due diligence to ensure that the vessel is only empoloyed between and at safe |

125 |

| |

places (which expression when used in this charter shall include ports, berths, wharves, docks, |

126 |

| |

anchorages, submarine lines, alongside vessels or lighters, and other locations including |

127 |

| |

locations at sea) where she can safely lie always afloat. Notwithstanding anything contained in |

128 |

| |

this or any other clause of this charter, Charterers do not warrant the safety of any place to |

129 |

| |

which they order the vessel and shall be under no liability in respect thereof except for loss or |

130 |

| |

damage caused by their failure to exercise due diligence as aforesaid. Subject as above, the |

131 |

| |

vessel shall be loaded and discharged at any places as Charterers may direct, provided that |

132 |

| |

Charterers shall exercise due diligence to ensure that any ship-to-ship transfer operations shall |

133 |

| |

conform to standards not less than those set out in the latest published edition of the |

134 |

| |

ICS/OCIMF Ship-to-Ship Transfer Guide. |

135 |

| |

(d) Unless otherwise agreed, the vessel shall be delivered by Owners dropping outward pilot at a |

136 |

| |

port in |

128 |

| |

____ |

138 |

| |

at Owners’ option and redelivered to Owners dropping outward pilot at a port in |

139 |

| |

____ |

140 |

| |

at Charterers’ option. |

141 |

| |

(e) The vessel will deliver with last cargo(es) of ____ and will redeliver with last cargo(es) of ____ |

142 |

| |

(f) Owners are required to give Charterers ____ days prior notice of delivery and Charterers are |

143 |

| |

required to give Owners ____ days prior notice of redelivery. |

144 |

37.39

Questions which may arise under Clause 4(a), Lines 110 to 120, of Shelltime 4 are dealt with in the earlier chapters of this book under Duration (), Lawful Merchandise () and Trading Limits (). Under Lines 115 and 116, trading is restricted to British Institute Warranty limits, but notwithstanding that, and subject to Clause 35 (the war risks clause), the charterers may order the ship not only to ice-bound ports but to ‘any part of the world’ outside Institute Warranty limits, provided that the owners consent and that the charterers pay any additional insurance premium. A general consent to trade outside the trading limits specified in the charter may not release the charterers from their obligations in regard to the safety of ports, even if they pay the premium required for breaching the limits: see paragraph , above. The position may however be different if the owners consent to go to a specified port.

37.40

Clause 4(b), Lines 121 to 124, grants to charterers the option to add off-hire periods to the end of the charter and stipulates that if that option is exercised, hire for the extra time is to be paid at the rate prevailing when the ship would otherwise have been redelivered, that is to say at the end of the primary charter period, rather than (if different) when the off-hire period occurred.

37.41

Clause 4(c), Lines 125 to 135, deals with the obligation upon the charterers to exercise due diligence to ensure that the ship is employed only between safe ports and places. This obligation, which is common to most tanker charters, is narrower than the usual obligation as to the safety of ports undertaken by charterers under dry cargo time charters. It may be overridden, so that an absolute undertaking is imposed after all, by unqualified language as to safety in the fixture recap: see The Greek Fighter [2006] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. Plus 99, per Colman, J., obiter, at [315]. If charterers fixing for trading within “safe ports” (or some equivalent shorthand) and incorporating Shelltime 4 terms intend Clause 4(c) to apply, they would be well advised to ensure that is spelt out in the recap. Where Clause 4(c) does apply, the exclusion of liability in respect of unsafety, except for loss or damage caused by charterers’ failure to exercise due diligence, together with “Subject as above” in Line 131, probably rules out a claim for an implied indemnity of the sort considered in , above, in the context of Clause 8 of the New York Produce form. (That point does not appear to have been considered in the case law. It could have arisen in The Chemical Venture, below, but it would seem that no claim on the basis of an implied indemnity was even put forward by the owners in that case.) It is suggested, however, that the restriction of the charterers’ responsibility to the exercise of due diligence does not mean that the master is obliged to use an unsafe port or berth, although it is perhaps possible to read Lines 131 and 132 literally as having that effect.

37.42

Where damages are sought by the owners under Clause 4(c) in respect of loss or damage resulting from an order to an unsafe port, the correct approach is to consider first whether the port is safe, applying the criteria laid down in The Eastern City , The Evia (No. 2) and other relevant authorities (see , above). If, on those criteria, the port is unsafe, the question then has to be considered whether the charterers have exercised due diligence: see The Saga Cob (C.A.), and The Chemical Venture , per Gatehouse, J., at page 510.

37.43

Due diligence in this context means the same as reasonable care; see The Saga Cob, above, per Parker, L.J., at page 551 and The Chemical Venture, per Gatehouse, J., at page 519. A due diligence clause thus protects charterers who do not know of the unsafety of the port unless prudent charterers, giving the matter careful consideration after due enquiry, would have concluded that the port was unsafe. In The Saga Cob, the Court of Appeal did not have to decide whether due diligence had been exercised, but expressed the opinion that even if the charterers know the facts giving rise to the risk that renders the port unsafe, it does not necessarily follow that they have failed to exercise due diligence. If the charterers order the ship to a port regarded generally by the owners as safe, the Court of Appeal considered that they might well be protected. But clearly charterers could only be protected in such circumstances if those owners who regard the port as safe also know the facts giving rise to the prospective unsafety. Moreover, the Court of Appeal’s observation should not be taken too far. First, a due diligence clause does not entitle charterers, who know or reasonably ought to appreciate that a port is unsafe, to decide for the owners that the degree of unsafety is such that the risk should be undertaken: see The Saga Cob, per Judge Diamond, Q.C., at page 408 of the first instance report. Second, if the charterers know the facts giving rise to the risk that renders a port unsafe, the natural inference may be that they ought to realise the port is unsafe, in which case (as in The Chemical Venture, below) they may be held in breach if they do not adduce evidence to justify their order. Third, it would not be sufficient for the charterers to adduce some opinions that the port was safe if there was evidence that other users, qualified to give an opinion, held a contrary view.

The

Saga Cob was time chartered on the Shelltime 3 form. Clause 3 of that form (the relevant part of which was similar to Clause 4(c) of the Shelltime 4) provided: “Charterers shall exercise due diligence to ensure that the vessel is only employed between and at safe ports… where she can always lie safely afloat, but notwithstanding anything contained in this or any other clause of this charter, Charterers shall not be deemed to warrant the safety of any port… and shall be under no liability in respect thereof except for loss or damage caused by their failure to exercise due diligence as aforesaid.”

The ship was to be employed under the charter in the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and East Africa for the carriage of clean petroleum products. In the course of the charter, she called about 20 times at Massawa without incident. On 26 August 1988 she was again ordered to proceed to Massawa, but while anchored off the port on 7 September she was attacked by armoured boats of the Eritrean Peoples’ Liberation Front (EPLF) – an anti-government guerrilla movement – and was damaged. Prior to this date there had been sporadic attacks on the town of Massawa, but insufficient to make it an unsafe port. As for attacks at sea, on 31 May 1988 another vessel had been attacked by EPLF boats 65 miles south of Massawa whilst in a convoy of which the

Saga Cob formed part. Thereafter,

Saga Cob was given a naval escort from time to time but no further attacks on shipping took place until 7 September 1988 and, apart from that one incident, there were no further attacks on shipping until January 1990.

It was held by Judge Diamond, Q.C., at first instance, that on the date the order was given, 26 August, Massawa was a prospectively unsafe port on the ground that there was on that date a foreseeable risk of seaborne attack by the EPLF which, while not involving a high degree of risk, was a risk which was more than negligible. He further held that since the charterers were aware of the facts and the relevant risks, they had failed to exercise due diligence. He said, at page 408, that the due diligence clause “does not entitle the charterer to treat on behalf of owners any degree of risk of danger to the vessel or crew as constituting an acceptable risk. Nor does the clause confer any discretion on the charterers to determine on behalf of owners whether a port is or is not safe. Nor does it entitle the charterer to decide on behalf of owners that the degree of unsafety is such that the risk ought to be undertaken.”

The Court of Appeal, reversing Judge Diamond, Q.C., held that Massawa was a safe port on 26 August and that the judge had adopted an incorrect test by asking whether the risk of attack was foreseeable. The fact that an attack was a foreseeable possibility did not make the risk of attack a characteristic of the port and did not prevent the actual attack on

Saga Cob from being an abnormal and unexpected event. The court emphasised the absence of any incident between May and August, the absence of any evidence that the naval escort system was in any way defective and the fact that there were no further attacks until January 1990, and concluded that the risk of guerrilla attack on ships using Massawa was not a characteristic of the port. In relation to due diligence, Parker, L.J., giving the judgment of the court, said, at page 551, that “if a charterer knows all the facts and orders the vessel to a port which is regarded generally by owners of vessels to be safe, he might well be protected’. On that basis, it might not be enough to show that the charterers should have concluded that there was a small but appreciable risk of attack and there was ‘at least a strong argument that the test [of want of due diligence] should be expressed thus – ‘if a reasonably careful charterer

would on the facts known have concluded that the port was prospectively unsafe’” (original emphasis).

The Saga Cob and

(C.A.).

(See also the comments on this case by Davenport in

.)

The Liberian tanker,

Chemical Venture, chartered on the Shelltime 3 form, was ordered to load at Mina al Ahmadi in Kuwait during the Iran/Iraq war. Shortly before the order was given, Iran had begun air attacks on any tankers using Saudi Arabian and Kuwaiti terminals. At first the master and crew refused to proceed, but helped by the owners with whom they exchanged several telex messages, the charterers eventually persuaded them to do so against payment of war bonuses. The ship was severely damaged by a missile from an Iranian warplane while in the channel leading to Mina al Ahmadi in which three other tankers had been similarly attacked in the previous 11 days (and in which 11 tankers of various flags were subsequently attacked during the next five months).

In the Commercial Court, Gatehouse, J., held that: (a) Clause 3 of the charter applied in the case of political as well as physical dangers; (b) Mina al Ahmadi was unsafe, Iranian air attacks being a normal characteristic of the approach voyage for a tanker, rather than abnormal or unexpected events; (c) the charterers, who knew the relevant facts, had failed to exercise due diligence and were in breach of Clause 3; but (d) what the owners had said (and not said) in their telex exchanges with the charterers while the crew bonuses were being arranged amounted to an unequivocal representation that they would not treat the orders to Mina al Ahmadi as a breach of Clause 3, and this prevented them from subsequently claiming damages from the charterers (but as to that see paragraph

, above).

The Chemical Venture .

Delegation of selection of berths

37.46

This is dealt with at and , above, but in the context of Clause 4 of the Shelltime 4 form, Timothy Walker, J., in Dow Europe v. Novoklav, below, in considering an argument on behalf of time charterers that the due diligence provision in Clause 4 should be construed “in the personal sense”, stated at page 309 of the report: “The short answer is, in my judgment, that this clause does not say so. The standard construction of a due diligence provision is that the obligation is one of due diligence ‘by whomsoever it may be done’ even if the obligation is delegated to an independent contractor (see The Muncaster Castle ; [1961] A.C. 807), unless this is ousted by clear words restricting the obligation to one of personal want of due diligence.” So an order given by time charterers for the ship to proceed to a particular port where the selection of the berth is in the hands of the port authority or terminal will, under Clause 4, make the charterers responsible for any want of due diligence as to the safety of the berth on the part of the port authority or terminal.

The

Alcina was time-chartered on the original Shelltime 4 form to Novoklav, who sub-chartered her to Dow. She was ordered by Novoklav to Arzew, which was controlled by Sonotrach, to load condensate. At the berth to which she was ordered by Sonotrach or the port authority, EPA, there was a fire and the ship suffered damage. Novoklav settled the claim of the owners and claimed over against Dow. As arbitrators found, the berth was unsafe because there was no emergency shutdown system in place and this was the cause of the accident. Dow argued that the settlement made by Novoklav was unjustified because their obligation under Clause 4 of the Shelltime 4 was no more than an obligation of due diligence in the selection of the port. It was found by arbitrators that both Sonotrach and EPA must have known of the deficiencies of the berth and their failure to exercise due diligence in regard to the safety of the berth was in law the failure of Novoklav. Timothy Walker, J., affirmed the arbitrators’ decision.

Dow Europe v.

Novoklav .

37.48 Clause 5 – Laydays/Cancelling

| 5. |

The vessel shall not be delivered to Charterers before |

145 |

| |

and Charterers shall have the option of cancelling this charter if the vessel is not ready and at their |

146 |

| |

disposal on or before |

147 |

37.49

This clause gives the charterers the option of cancelling if the ship is not ready and at their disposal before the stipulated date. The state of readiness required is, no doubt, that set out in Clauses 1(a) to (h) and 2(a)(i) to (iv) of Shelltime 4. For general comments on readiness and cancelling clauses, see , 8 and 24.

37.50

The cancelling clause in the Essotime form in The Arianna was in somewhat similar terms to that of the Shelltime form. The charter provided:

“3. … hire to commence when written notice… has been given… that the vessel… being then ready… and in every way fitted for the service and the carriage of see Clause 57, and being on delivery tight, staunch and strong… with pipe lines, pumps and heater coils in good working condition, so far as the same can be attained by the exercise of due diligence…

4. … Charterer shall have liberty to cancel this Charter should Vessel not be ready in accordance with the provisions hereof…

57A. The vessel to be employed in general product trading with all liquid cargoes that can safely be handled by product tankers…

69. Owner to at all times maintain tank cleaning system in good order such that 6 machines can run simultaneously, at sea water temperature of 180´F at 170 P.S.I. pressure.”

37.51

The facts of the case are set out under Clause 1, above, at paragraph . One of the questions which arose was whether the charterers were entitled to cancel by reason of the fact that the ship was unable to comply with Clause 69 at the time of delivery. In considering the cancelling clause, Webster, J., said, at page 387: “It is common ground that the charterers’ right to cancel the charter depends, in the first instance, upon the proper construction of cl. 4. [Counsel], on behalf of the charterers, contended that the reference in cl. 4 to ‘the provisions hereof’ was to be taken as a reference to all the provisions of the charter-party (which would include a number of very detailed provisions contained in cl. 80), and that in particular it constituted a reference to cl. 69. I reject that contention. In my view, the words ‘ready in accordance with the provisions hereof’ in cl. 4 are to be construed as a reference to the provisions of cl. 3; and, in my view, those words are to be taken as a reference, therefore, to the words in cl. 3 beginning at the words ‘then ready’ and ending at the words ‘attained by the exercise of due diligence’. This was the conclusion of the arbitrators… with which I respectfully agree.”

37.52

The arbitrators in their award, which was appealed to the Commercial Court, had stated: “The charterers argued that the words in Clause 4, ‘ready in accordance with the provisions hereof” meant that the vessel as tendered had to satisfy every provision of the charter which could be applicable at the delivery date. We do not agree with this very wide construction of the cancelling clause in this charter. In our view this cancelling clause is specially related to those provisions of the charter dealing with readiness for delivery. The Clause is only intended to give an option to cancel if the vessel is not ready for delivery by the cancelling date. The particular term as to readiness for delivery is Clause 3, and in our view the Charterer is only entitled to cancel under Clause 4 if the vessel does not satisfy the provisions as to readiness for delivery specified in Clause 3.”

37.53

In the particular circumstances of the case it was held that the charterers were not entitled to cancel: see under Clause 1 above.

37.54 Clause 6 – Owners to Provide

| 6. |

Owners undertake to provide and to pay for all provisions, wages (including but not limited to all |

148 |

| |

overtime payments), and shipping and discharging fees and all other expenses of the master, officers |

149 |

| |

and crew; also, except as provided in Clauses 4 and 34 hereof, for all insurance on the vessel, for all |

150 |

| |

deck, cabin and engine-room stores, and for water; for all drydocking, overhaul, maintenance and |

151 |

| |

repairs to the vessel; and for all fumigation expenses and de-rat certificates. Owners’ obligations under |

152 |

| |

this Clause 6 extend to all liabilities for customs or import duties arising at any time during the |

153 |

| |

performance of this charter in relation to the personal effects of the master, officers and crew, and in |

154 |

| |

relation to the stores, provisions and other matters aforesaid which Owners are to provide and pay for |

155 |

| |

and Owners shall refund to Charterers any sums Charterers or their agents may have pad or been |

156 |

| |

compelled to pay in respect of any such liability. Any amounts allowable in general average for wages |

157 |

| |

and provisions and stores shall be credited to Charterers insofar as such amounts are in respect of a |

158 |

| |

Period when the vessel is on-hire. |

159 |

37.55 Clause 7 – Charterers to Provide

| 7. |

(a) Charterers shall provide and pay for all fuel (except fuel used for domestic services), towage |

160 |

| |

and pilotage and shall pay agency fees, port charges, commissions, expenses of loading and |

161 |

| |

unloading cargoes, canal dues and all charges other than those payable by Owners in |

162 |

| |

accordance with Clause 6 hereof, provided that all charges for the said items shall be for |

163 |

| |

Owners’ account when such items are consumed, employed or incurred for Owners’ purposes or |

164 |

| |

while the vessel is off-hire (unless such items reasonably relate to any service given or distance |

165 |

| |

made good and taken into account under Clause 21 or 22); and provided further that any fuel |

166 |

| |

used in connection with a general average sacrifice or expenditure shall be paid for by Owners. |

167 |

| |

(b) In respect of bunkers consumed for Owners’ purposes these will be charged on each occasion |

168 |

| |

by Charterers on a “first-in-first-out” basis valued on the prices actually paid by Charterers. |

169 |

| |

(c) If the trading limits of this charter include ports in the United States of America and/or its |

170 |

| |

protectorates then Charterers shall reimburse Owners for port specific charges relating to |

171 |

| |

additional premiums charged by providers of oil pollution cover, when incurred by the vessel |

172 |

| |

calling at ports in the United States of America and/or its protectorates in accordance with |

173 |

| |

Charterers orders. |

174 |

37.56

For general comments on such clauses, see , above. For observations on the obligation of charterers to provide and pay for agency fees in Clause 20 of the Beepeetime 2 charter, see The Sagona and paragraph , above.

37.57 Clause 8 – Rate of Hire

| 8. |

Subject as herein provided, Charterers shall pay for the use and hire of the vessel at the rate of United |

175 |

| |

States Dollars per day, and pro rata for any part of a day, from |

176 |

| |

the time and date of her delivery (local time) to Charterers until the time and date of redelivery (local |

177 |

| |

time) to Owners. |

178 |

37.58

The stipulation that local time shall be used in the computation of hire avoids the difficulties of construction in charters which contain no such express stipulation: see The Arctic Skou and , above. It is supplemented by a general requirement in Clause 21(f) that all references to “time” in the Shelltime 4 form are references to local time, if nothing to the contrary is stated. For a definition of “delivery”, see paragraphs I.13, I.35 and , above, and for comments on redelivery, paragraphs I.13, I.37 and .

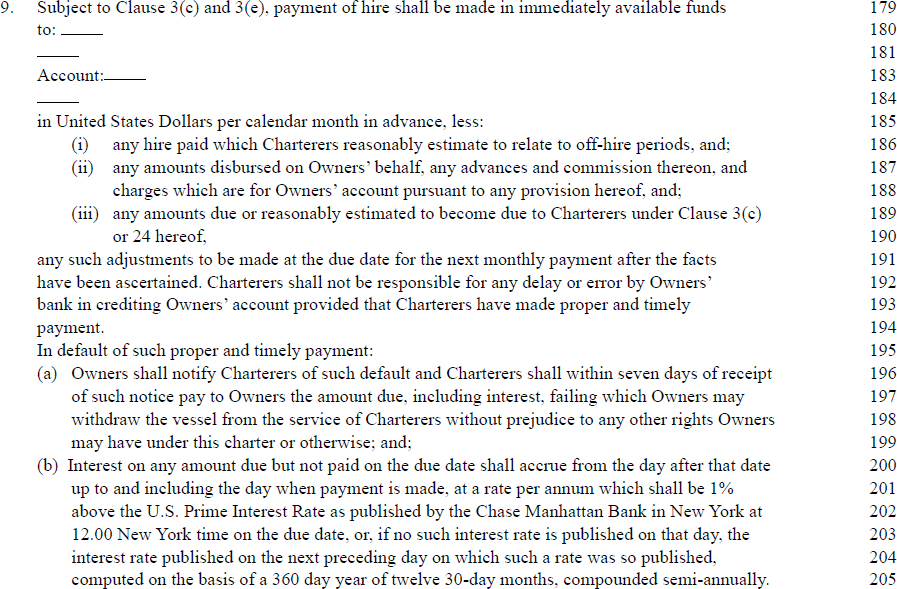

37.59 Clause 9 – Payment of Hire

37.60

General comments on payment of hire and withdrawal are to be found in , above.

37.61

The obligation to pay hire is subject to Clause 3(c), which entitles the charterers to make no further hire payments in certain circumstances when the owners have breached their maintenance obligations, and Clause 3(e), which entitles the charterers to put the ship off hire in certain circumstances following a failed inspection of the ship. Payment of hire is to be made in “immediately available funds”. This terminology does not exactly reflect the definition in the authorities of the equivalent of a cash transfer, namely a transfer which gives the owners an unconditional right to the immediate use of the funds transferred: see The Brimnes , (C.A.) and The Chikuma (H.L.), paragraph , above. In The Chikuma the funds transferred were immediately available, but were held not to be unconditional and thus not the commercial equivalent of cash; see paragraph , above.

37.62

Under Clause 9(i) the charterers cannot make any deduction from a hire payment in respect of anticipated off-hire, even if the ship is off hire at the time the hire payment is due, since a deduction can be made only in respect of “any hire paid”. This is different from the position which has been said to pertain under charters in which the off-hire clause provides that ‘the payment of hire shall cease’ when time is lost from the specified causes: see The Lutetian and and , above.

37.63

However, under Clause 9(iii), the charterers may deduct amounts due or reasonably estimated to become due in the future under either of two other provisions. The provisions in question are identified as Clause 3(c) and Clause 24. Clause 24 is the Shelltime 4 speed and performance regime, so this makes sense (and indeed makes sense of Clause 24(b); see paragraph , below). The reference in Clause 9(iii) to Clause 3(c), however, does not make sense. In the original Shelltime 4, the reference was to Clause 3(b) (or, rather, Clause 3(ii), as it was then). Since Clause 3(c) is already catered for, within Clause 9, by the opening words in Line 179, and is not sensible in Clause 9(iii), it is thought the reference to it in Line 189 is to be interpreted as a typographical error for Clause 3(b). Then Clause 9(iii) has the effect, for example, that if a breach of Clause 10 deprives the charterers of space to which they are contractually entitled, they may deduct the value of the unavailable space from advance hire payments.

37.64

Lines 192 and 193, providing that the charterers shall not be responsible for any delay or error on the part of the owners’ bank, merely serve to emphasise that the charterers are responsible, as between themselves and the owners, for any delay or error on the part of their own bank. In default of “proper and timely” payment, the owners do not have an immediate right to withdraw, but under Clause 9(a) must give seven days’ notice before doing so. A valid notice cannot be given until after the time for payment has expired, which means after 2400 hours on the due date at the place where payment is to be made: see The Afovos (H.L.) and paragraph , above. Following the giving of a valid notice, the charterers have seven days within which to make payment, but in addition to the hire due, they must also pay interest calculated in accordance with Clause 9(b) and only that full payment, that is to say, including interest, will prevent the owners from becoming entitled to withdraw.

37.60

General comments on payment of hire and withdrawal are to be found in , above.

37.61

The obligation to pay hire is subject to Clause 3(c), which entitles the charterers to make no further hire payments in certain circumstances when the owners have breached their maintenance obligations, and Clause 3(e), which entitles the charterers to put the ship off hire in certain circumstances following a failed inspection of the ship. Payment of hire is to be made in “immediately available funds”. This terminology does not exactly reflect the definition in the authorities of the equivalent of a cash transfer, namely a transfer which gives the owners an unconditional right to the immediate use of the funds transferred: see The Brimnes , (C.A.) and The Chikuma (H.L.), paragraph , above. In The Chikuma the funds transferred were immediately available, but were held not to be unconditional and thus not the commercial equivalent of cash; see paragraph , above.

37.62

Under Clause 9(i) the charterers cannot make any deduction from a hire payment in respect of anticipated off-hire, even if the ship is off hire at the time the hire payment is due, since a deduction can be made only in respect of “any hire paid”. This is different from the position which has been said to pertain under charters in which the off-hire clause provides that ‘the payment of hire shall cease’ when time is lost from the specified causes: see The Lutetian and and , above.

37.63

However, under Clause 9(iii), the charterers may deduct amounts due or reasonably estimated to become due in the future under either of two other provisions. The provisions in question are identified as Clause 3(c) and Clause 24. Clause 24 is the Shelltime 4 speed and performance regime, so this makes sense (and indeed makes sense of Clause 24(b); see paragraph , below). The reference in Clause 9(iii) to Clause 3(c), however, does not make sense. In the original Shelltime 4, the reference was to Clause 3(b) (or, rather, Clause 3(ii), as it was then). Since Clause 3(c) is already catered for, within Clause 9, by the opening words in Line 179, and is not sensible in Clause 9(iii), it is thought the reference to it in Line 189 is to be interpreted as a typographical error for Clause 3(b). Then Clause 9(iii) has the effect, for example, that if a breach of Clause 10 deprives the charterers of space to which they are contractually entitled, they may deduct the value of the unavailable space from advance hire payments.

37.64

Lines 192 and 193, providing that the charterers shall not be responsible for any delay or error on the part of the owners’ bank, merely serve to emphasise that the charterers are responsible, as between themselves and the owners, for any delay or error on the part of their own bank. In default of “proper and timely” payment, the owners do not have an immediate right to withdraw, but under Clause 9(a) must give seven days’ notice before doing so. A valid notice cannot be given until after the time for payment has expired, which means after 2400 hours on the due date at the place where payment is to be made: see The Afovos (H.L.) and paragraph , above. Following the giving of a valid notice, the charterers have seven days within which to make payment, but in addition to the hire due, they must also pay interest calculated in accordance with Clause 9(b) and only that full payment, that is to say, including interest, will prevent the owners from becoming entitled to withdraw.

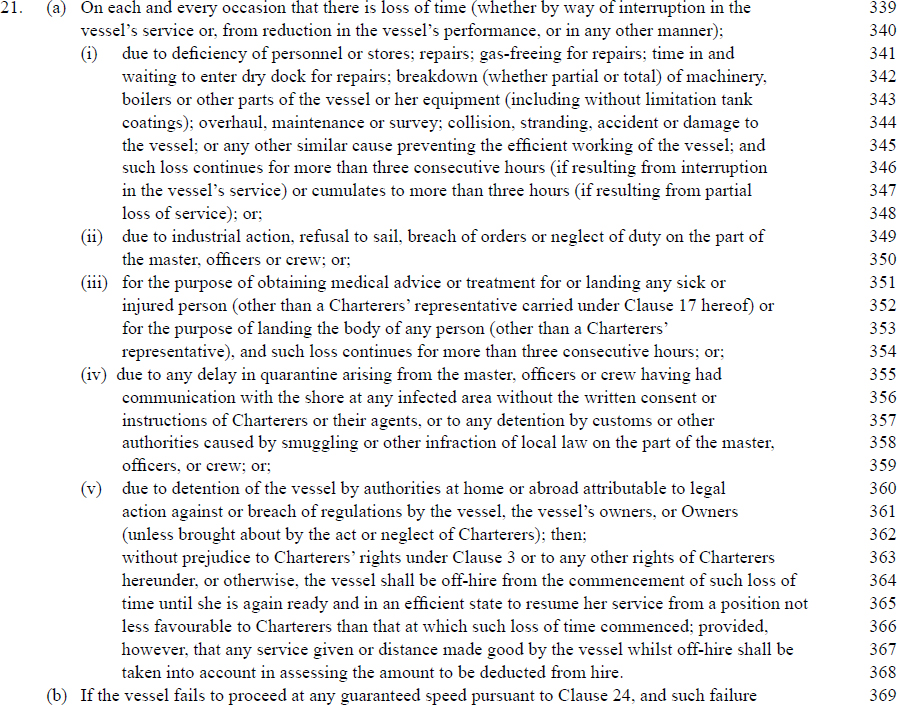

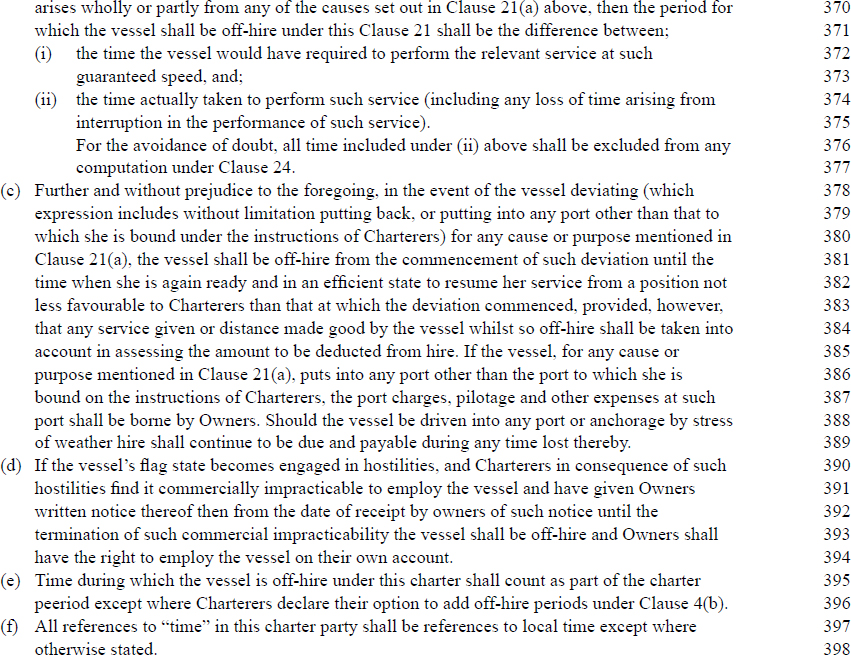

37.65 Clause 10 – Space Available to Charterers

| 10. |

The whole reach, burthen and decks on the vessel and any passenger accommodation (including |

206 |

| |

Owners’ suite) shall be at Charterers’ disposal, reserving only proper and sufficient space for the |

207 |

| |

vessel’s master, officers, crew, tackle, apparel, furniture, provisions and stores, provided that the |

208 |

| |

weight of stores on board shall not, unless specially agreed, exceed ____ tonnes at any time during the |

209 |

| |

charter period. |

210 |

37.66

If the owners are in breach of Clause 10, the charterers have a right under Clause 3(b) to a reduction of hire, apart from any other remedy they may have for breach: see The Fina Samco and (C.A.). It is thought they may also be able to deduct from advance hire the value of the space not available to them, although this requires recognition of a typographical error in the standard form at Line 189: see under Clause 9(iii) above.

37.67 Clause 11 – Segregated Ballast

| 11. |

In connection with the Council of the European Union Regulation on the Implementation of IMO |

211 |

| |

Resolution A747(18) Owners will ensure that the following entry is made on the International Tonnage |

212 |

| |

Certificate (1969) under the section headed “remarks”: |

213 |

| |

“The segregated ballast tanks comply with the Regulation 13 of Annex 1 of the |

214 |

| |

Convention for the prevention of pollution from ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 |

215 |

| |

relating thereto, and the total tonnage of such tanks exclusively used for the carriage of segregated |

216 |

| |

water ballast is ____ The reduced gross tonnage which should be used for the calculation |

217 |

| |

of tonnage based fees is ____”. |

218 |

37.68 Clause 12 – Instructions and Logs

| 12. |

Charterers shall from time to time give the master all requisite instructions and sailing directions, and |

219 |

| |

the master shall keep a full and, correct log of the voyage or voyages, which Charterers or their agents |

220 |

| |

may inspect as required. The master shall when required furnish Charterers or their agents with a true |

221 |

| |

copy of such log and with properly completed loading and discharging port sheets and voyage reports |

222 |

| |

for each voyage and other returns as Charterers may require. Charterers shall be entitled to take copies |

223 |

| |

at Owners’ expense of any such documents which are not provided by the master. |

24 |

37.69

See generally on this subject , above. See also , above.

37.70

There may be circumstances in which it may be reasonable for the owners or the master not to comply with instructions immediately. In The Houda , the facts of which are set out under Clause 13, below, the ship was chartered on the original Shelltime 4 form and was issued by the charterers with standing instructions stating: “All instructions relating to the voyages of your vessel will be issued by Kuwait Petroleum Corp. in Kuwait.’ When, following the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq, voyage instructions were received by the ship from London, the owners declined to comply with them, questioning whether the instructions were lawful since they did not originate from Kuwait. It was held by the Court of Appeal that in principle owners under a time charter might be entitled to a reasonable time to consider the implications of obeying instructions if they had reasonable doubts about the lawfulness of the orders. Neill, L.J., said, at page 549: ‘It is not of course for this Court to decide whether on the facts the owners had reasonable grounds to pause, but I am satisfied that in a war situation there may well be circumstances where the right, and indeed the duty, to pause in order to seek further information about the source of and the validity of any orders which may be received is capable of arising even if there may be no immediate physical threat to the cargo or the ship.”

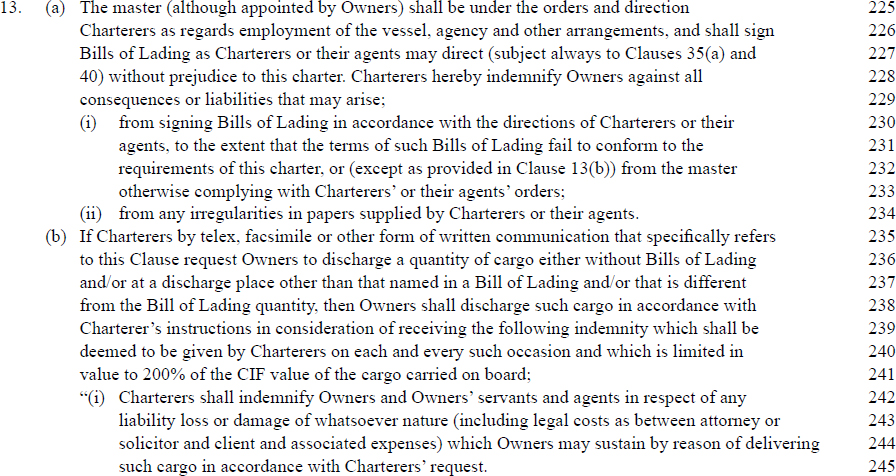

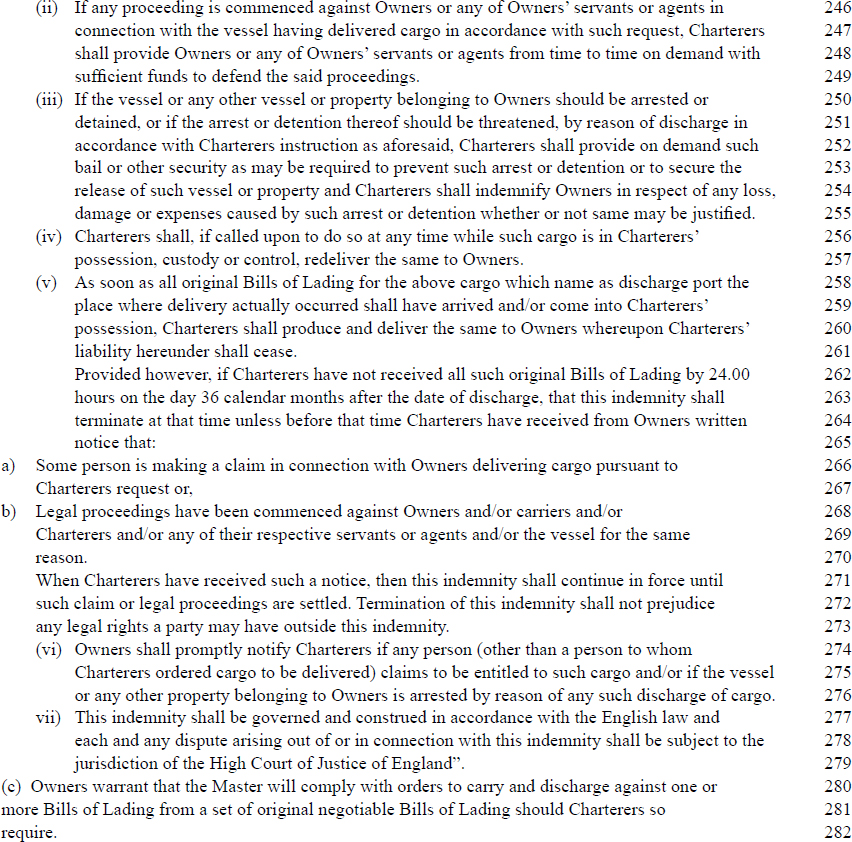

37.71 Clause 13 – Bills of Lading

37.72

The stipulation that the master shall be under the orders and directions of the charterers is dealt with in , above. For comments on the signing of bills of lading “without prejudice to this charter”, see paragraph , above and for signature of bills of lading generally, see , above.

37.73

The fact that under Clause 13(a) the master is under the orders and directions of the charterers does not mean that the master or owners must necessarily comply immediately with such orders: see The Houda, , above, and , below. Clause 13(a) contains an express indemnity. Some tanker time charters contain no express indemnity. As to the indemnity normally implied in favour of the owners against the consequences of complying with the charterers’ orders, see et seq., above.

37.74

In The Berge Sund (C.A.), the detailed facts of which are set out at and , below, the charter was not on a standard form although it contained many terms common to standard form tanker time charters. The charter in that case contained no express indemnity although it provided, as is common: “Master, although appointed by, and in the employ of Owner, and subject to Owner’s direction and control, shall observe the orders of the Charterer as regards employment of the Vessel, Charterer’s agents or other arrangements required to be made by Charterer hereunder.” It further provided by the off-hire clause that in the event that a loss of time “not caused by Charterer’s fault” should continue, due to a number of stated causes, for more than 24 hours, the vessel should be off hire. The charterers claimed that the ship was off hire during a period of abnormally lengthy tank cleaning following the carriage of a cargo of off-specification or contaminated cargo. One of the arguments advanced by the owners was that since there was no fault on their part, or on the part of the crew, and since the abnormally lengthy tank cleaning required was a consequence of the charterers’ order to load the cargo, they were entitled to be reimbursed the amount of off-hire by the charterers (if the vessel was off hire) pursuant to an implied indemnity. The charterers’ response was that any implication of an indemnity was inconsistent with the terms of the off-hire clause and the arbitrators accepted the charterers’ argument. Steyn, J., at first instance (, at page 467) took a different view from the arbitrators on the implication of an indemnity, but concluded that in any event the delay which was the subject of the off-hire claim was not directly caused by the charterers’ orders. In the Court of Appeal, Staughton, L.J., expressed the view, obiter, that the implication of an indemnity under the charter in that particular case was inconsistent with the exception of “Charterer’s fault” in the off-hire clause. He said, at page 462 of the Court of Appeal report: “Whatever the correct meaning of the exception of charterers’ fault, it is, as it seems to me, expressly dealing with the circumstances in which conduct by the charterers will prevent the vessel being off hire. That in my opinion excludes any implied term that the charterers will indemnify the owners against loss of hire under the clause caused by compliance with the charterers’ orders, if there has not been charterers’ fault.” (Compare The Marie H , the facts of which are set out at paragraph , above, in which Timothy Walker, J., held that the owners were entitled to be indemnified in respect of off-hire caused by the charterers’ loading, at their risk, dangerous cargo; the off-hire clause reading “should the vessel put back whilst on voyage by reason of an accident or breakdown, for which Charterers are not responsible…”.) Staughton, L.J., also agreed with Steyn, J.’s conclusion that there was no evidence that the delay had been directly caused by the charterers’ orders.

37.75

Under Clause 13(a)(ii) the owners are entitled to an indemnity against all consequences arising from “irregularities in papers supplied by the Charterers or their agents”. In The Boukadoura , Evans, J., held that a bill of lading that overstated the quantity of oil shipped was an ‘irregularity’ within the meaning of a similar provision in Clause 20(a) of the STB Voy form: see paragraph for a fuller statement of the facts of the case.

37.76

In the original Shelltime 4, Clause 13(b) entitled the owners to “an indemnity in a form acceptable to” them before they could be required to discharge other than at the bill of lading destination against presentation of an original bill of lading. It is suggested that under such open-ended wording, which may still be encountered in other tanker charter forms, the indemnity which the owners may require must be reasonable in amount, having regard to the potential liability to which the owners might be exposed, but that so far as concerns the form of indemnity, they are required to do no more than act bona fide in deciding whether the indemnity is acceptable or not: see Astra Trust v. Adams , per Megaw, J., at page 87, The John S. Darbyshire , per Mocatta, J., at page 466, and B.V. Oliehandel Jungkind v. Coastal International , per Leggatt, J., at page 469. It is suggested that this might mean, for instance, that the owners could insist that the indemnity be given or countersigned by a bank, P. & I. Club or other strong surety.

37.77

Now, however, Shelltime 4 obliges the owners to discharge against only an indemnity from the charterers themselves, in the terms set out in Clause 13(b). It would seem, therefore, that if the owners have concern as to the charterers’ creditworthiness on such an indemnity they must seek to address that at the outset by negotiating an amendment to the standard form or an additional clause.

37.78

Clause 13(b) governs when the owners are obliged to discharge a quantity of cargo without presentation of an original bill of lading, or at a place other than the bill of lading destination or being a quantity other than the bill of lading quantity. In the case which follows, on the original Shelltime 4 form, Clause 13(a) had been amended and Clause 13(b) deleted. The question arose whether, in the absence of contractual provision, the owners and the master could refuse to comply with orders of the charterers to discharge cargo without production of bills of lading, even in circumstances where such discharge involves no infringement of the rights of the parties entitled to the possession of the cargo.

37.72

The stipulation that the master shall be under the orders and directions of the charterers is dealt with in , above. For comments on the signing of bills of lading “without prejudice to this charter”, see paragraph , above and for signature of bills of lading generally, see , above.

37.73

The fact that under Clause 13(a) the master is under the orders and directions of the charterers does not mean that the master or owners must necessarily comply immediately with such orders: see The Houda, , above, and , below. Clause 13(a) contains an express indemnity. Some tanker time charters contain no express indemnity. As to the indemnity normally implied in favour of the owners against the consequences of complying with the charterers’ orders, see et seq., above.

37.74